By Junior Knox

The inside of an atom is mostly just empty space, and now you know how this story ends.

I wore a gray knit dress to the Roxy to protect myself from the empty space; from the cold in the dead of a Buffalo winter. In simpler times, the Roxy was unpretentious games of pool and ten 19-year-olds squeezing together around a karaoke mic for Bon Jovi. Now, it is more cocaine than camaraderie, more salaciousness than celebration, but some stories just require the glory of a dive bar and my tongue in a stranger’s mouth.

I ordered gin and tonics.

In certain corners where unpretentious pool was still played, Kelly was the wild-haired brunette that paused to make eye-contact before flicking her wrist and connecting the cue with the ball. She set her cue down and approached, flipping her curly hair back with both hands.

“Hi,” she said.

“Hey,” I replied, sipping my gin and tonic.

“Can I buy you a drink?”

“I already have one,” I said, shaking it so the ice sloshed around, cube against cube, atoms hitting atoms.

“When you’re finished?”

It seemed a direct relationship, then, that the less gin and tonic I had in my glass, the closer we moved to each other, her arm first around my waist, then my hands in her hair, and finally, her lips to my earlobe.

“What was your name again?” She murmured.

She leaned over the bar, and after a minute, held another drink out to me with hands that were fragrant with the scent of her hair. My own hands took away the warm earth scent; natural and clean.

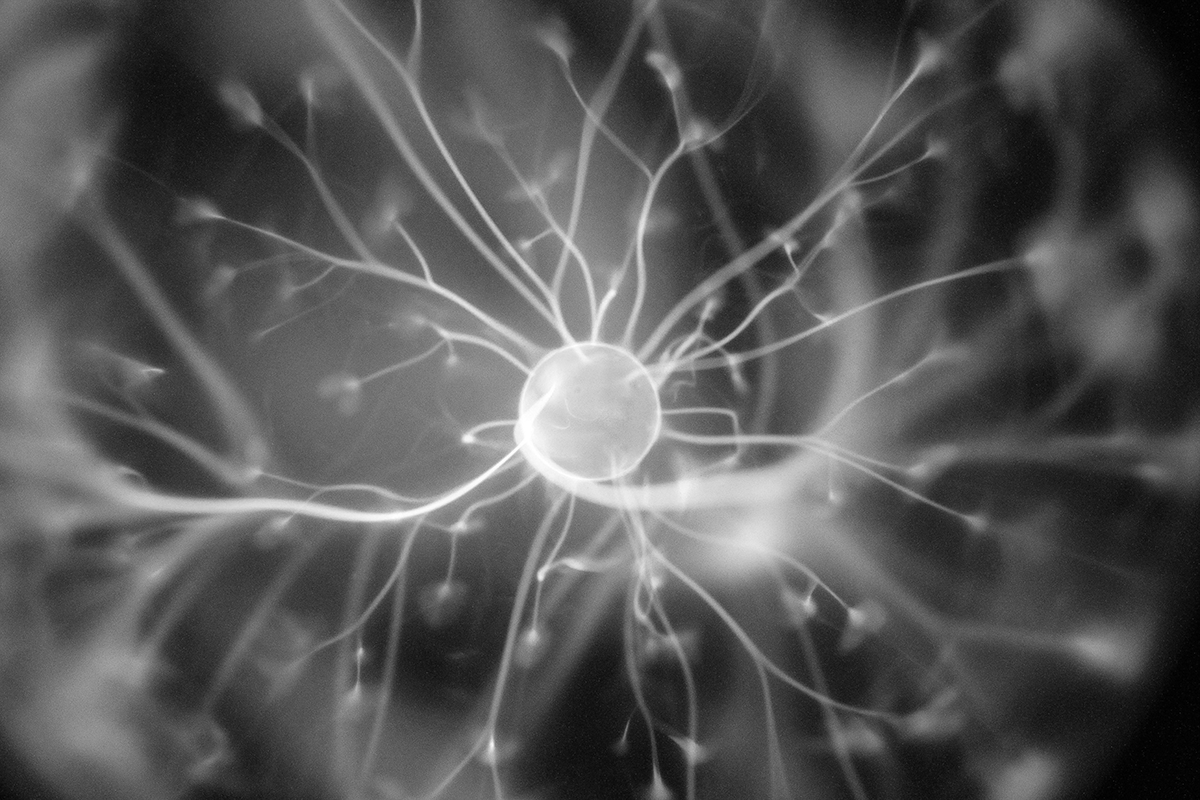

I drank, and told her my story. I drank, and tipped the strippers on top of the bar as she tipped her head back for free tequila. I drank, and danced with her, white arms outstretched in a dark room, floating and trailing brightness like an acid trip. I drank, and when I kissed her I tasted whisky and garlic.

“You’re pretty like an alien,” she said, and I went home with her.

***

It was a Sunday later that week, and I’d had two glasses of wine.

I watched Kelly as she settled back on her bed. I had already noticed how often she would throw her head downward in that exaggerated motion, grab her hair with both hands, and toss her great mass of brunette curls back behind her head. It seemed, then, that movement was her neutral state, and I was there learning how to dance.

In her room, an open suitcase was on the floor, overflowing with clothing. She was visiting from New York City for the holidays, she explained, and hadn’t bothered to unpack or separate dirty laundry from clean. It was her old room in her childhood home, and that would have been obvious even if she hadn’t told me. Family photos and old trophies lined the walls and the shelves.

She bounced up from the bed to show me her softball pictures.

“I used to be a blonde!”

I could barely spot her as she pointed to the photo before she tossed it aside and picked up a worn Stephen King paperback.

“Do you read?”

She sat back down next to me on the bed and began to flip through the pages. I watched her hands, bone beneath flesh, as they flexed and curled in such a way that the tiny creases in her skin seemed to disappear. I watched her thumb let loose one page at a time, until I looked up and realized she wasn’t looking at the book at all.

My nose inches from her nose, I felt like I should have something to say. Instead I waited, breathing, taking in the scent of childhood homes and softball trophies mixed with earth and ozone and New York City.

She laughed, so I laughed, too.

“I’m really reaching here,” she said, and only then did it dawn on me that she was waiting to be kissed.

I kissed her slightly open lips. It was imperfect, and our teeth connected. She laughed, so I laughed, too.

***

For the next several days, it was bars and coffee shops and ski-jacketed passersby breathing moist clouds into the cold Buffalo air outside the windows. I tried to count the seconds just to slow the minutes down, but the sunlight faded anyway.

I can see us as if we had been caught on a time-lapse camera. The sun zooms over us as blurs enter and exit around us, chattering nonsensically and gesturing wildly and spilling coffee that dries at once in sticky puddles.

Kelly jerks her head to look at me and bats her eyelashes rapidly and her hands move on my arms and pull on my clothing and caper with the disposable coffee cups until she has broken them down into their fundamental components of paper and plastic and cardboard.

Eventually, the film slows as my memory catches up.

“Let’s go to my place,” she said, because her bedroom was our reward for burning daytime. I drove, and she messed with the knobs on my radio, and we found a song to remind us of each other.

I sang to her as we pulled up into the driveway. I sang as the stairs to her room spun under my feet.

“Just put your hands on me and hold me,” she replied. “Just put your fingers in me and hold me just like that.”

I did as she asked, blood moving from my core to fill my capillaries and light my extremities like a forest fire. If I failed, that night, to rescue limbs and hair and fragrant hands and gray knit dresses, it’s only because the compound molecules in volatile gases were bursting apart, and there was not enough whisky or wine or flesh or tongue to absorb the energy that resulted.

“I don’t know what to do,” Kelly said, and I wondered what could cause such concern, if I’d somehow spilt my emotions around us, crimson and sticky and staining, or if it was my arms tangled in hers like roots gone wild.

It didn’t matter anyway, because the women just came to her.

“The women,” she said. “They just come to me.”

It was a warning, and I knew this, even as I bloomed like poppies out of place on white linen.

“This isn’t what I do,” I said, but I didn’t mean it.

What else could be said? She had the best intentions.

“I have the best intentions,” she said. “There’s not a mean bone in my body. Ask my family,” she said. “Ask my friends.”

“Will you think of me when you’re in Atlanta?” She asked.

“Does it matter?” I said, but I didn’t mean it. I’d already given her what she wanted and the rest was just my undignified heart pumping undignified blood and neural patterns firing away, confusing pleasure and love and sex and infatuation.

It was the small hours of New Year’s Day when the affair came to an end. I had spent the night fighting sleep, alternating between accidental slips into slumber and inhaling the earth; the sweat and the sweetness and the sex implied by the scent of the curly mane spread out on the pillow next to me.

She had hinted the night before that I should be gone before her parents woke up, so at six a.m. I reached over the side of the bed to find my pants. I looked over at Kelly, her eyes closed, bare back flawless in the dim light. I pushed myself off to lift myself off the bed, and she reached over and grabbed my arm. Pulled me back to her, her mouth next to my ear.

“No,” she said. “Stay. Never leave, never leave.”

Did I leave? I must have. I awoke sometime later in the day, in the guest bedroom at my mother’s house. I put my hands up to my face and breathed deep.

***

I came back to Atlanta a scientist.

I tried to replicate the experiment. I tried to duplicate the chain of code, to unlock the combination that would yield the eccentric whose hair I could wrap around my fingers in a curly knot.

I came back to Atlanta an artist.

I lived in a one-bedroom apartment with bare white walls and beige carpet. I tried to paint the walls a crimson grid to match the brick of Brooklyn, white-outlined and stained with graffiti and bird shit.

I came back to Atlanta a storyteller.

I saw every picture of her girlfriends, those she rode through Manhattan on the back of her scooter, those she took to Europe, those she sunned herself bronze with on the beach. I planted her in every corner of my apartment, and when she grew, we traveled, too, from one room to the next. My ceiling was decorated with our slide-show when I would lie on my back and project us from my skin.

I came back to Atlanta an asshole.

The women, they were pretty like aliens, like grasshoppers, they tasted of seawater and cigarettes and some of cherry Chap Stick. I don’t remember their last names, but I remember the patterns their fingers traced on my back as I fell asleep.

Emma had curly hair and wide eyes and a Jersey accent. We pillow-talked about women and heartbreak and the city. I told her I didn’t want a relationship. Donna was big, pretty, and Jewish. Dark-haired and dark-complected. We slept together a handful of times until I made a joke in poor taste. We stopped seeing each other. Amy was African-American. Her nipples were pierced and she had a tattoo on the small of her back. She could have been a model but she was short. She told me she didn’t believe in love. Marilyn was three years younger than me and had just come out to her parents. We had very little in common but she fell in love with me anyway. She told me this via email after I broke her heart. Hannah was a skinny blonde who wore too much makeup. I took her out with my friends and she drank until she couldn’t stand up anymore. When I told her she couldn’t come home with me again, she spat in my face. Natalie was tall, taller than any girl I’d ever been with. I called her “girlfriend” for a little while. Together, we counted out how many we’d had, and I felt ashamed. We tried to stay friends but it didn’t work out. I never slept with Michelle but I may have teased at it. Eventually, I started breaking our plans. She emailed and called and sent me texts, and then she stopped.

Some had freckles. Some had moles. Some had birthmarks. Some didn’t shave. Some had terra-cotta-colored nipples and invisible areola and coral hair between their legs. Some wanted more than one night; some didn’t want anything more at all. They were teachers and nurses. They were accountants and account managers. They worked retail and government jobs. Some were artists, some were writers. Maybe they wrote about chemistry and oxygen and compound molecules bursting apart.

I cut my hair off, then I let it grow some more. I bought a scooter so I could feel the wind rush by my face as I zipped through traffic in the city. I met girls in bars and introduced myself as “Junior,” and when they put their hands in my hair, I put my lips to their ears and told them about the light and the noise and the pavement that radiates warmth even at night in New York.