By Liesel Sloan

April 3, 1978 — This is what is clear to me:

A classroom full of giggling, awkward 11-year-olds facing an equally anxious, and definitely not amused teacher, on the first day of the first time Baltimore County required Co-Ed Sex Education. Something forgotten, per usual, allowed me a brief escape to my locker. Our classroom was located last on the left of a single long hallway and, from that perspective, I saw her walking toward me with the principal at her side.

Immediately, in only the way a child can spot their mother from 1,000 yards, I knew who the woman in the tan London Fog trench coat was, and I knew someone was dead.

My grandfather, her father, had died only two months before, and, having seen her then, I must have recognized the walk, the face, the aura of my mother in grief. Even with this knowledge I was naive, unprepared for her words spoken as she continued guiding me to the exit.

“I need you to be strong for me. I need you to be strong for me.”

I don’t remember the last time I saw my father.

Did I stop running around to say good-bye? Did I tell him I hoped he had fun with his friends? I think perhaps I spoke on the phone to him during a time when long-distance calls from traveling parents were rare and expensive.

Maybe I told him I loved him; I hope so.

“Daddy’s dead,” she said.

Of course tears came; the explanation of the plane crashing into the Nassau Harbor.

“They’re dead. They’re all dead.”

I was placed in the middle of the front seat between my mother and…someone. This was the time when all the mothers drove large, wood-paneled station wagons and seat belts were optional.

We still had to pick up my brother, Kurt, from his school, and eventually I was left in the front, still pressed against this person who is nothing but a shadow in my memory.

My mother and Kurt now in the back, we drove to my grandmother’s house. There was no talking, no radio; only the broken half-man, half boy sobs of a 14-year-old. My brother, always bigger, always better, always braver, never cried, and I wished nothing more than to comfort him. No thought for my mother, not one.

To this day I am ashamed of this, but perhaps it was easier for me to understand the impact of this moment on my brother. How could I know then what it means to lose a partner, a best friend, a breadwinner?

Daddy’s death made the news. Just as today, five prominent businessmen, twisted wreckage, body recovery, makes good copy and great visuals, with the face of the broadcaster appropriately solemn.

There was pressure to get to his parents’ house before 6 p.m., so they would hear it first from Mom, be prepared when all the friends of the family began to call in shock or only to seek the juicy details in the safety of viewing tragedy from afar. I didn’t go with my mom and brother, but stayed home alone, hidden in a bedroom. This was probably seen as selfish, callous, but I believed, with my whole heart, that the news would immediately kill them.

It didn’t, of course; you don’t live to be in your 70’s, through two World Wars and the Depression without experiencing great losses and continue to keep breathing whether you want to or not. Did I choose well? Was it better to only hear of my grandfather falling to the ground unconscious, my grandmother’s scream so piercing it brought the neighbors to the door than to see it?

There followed the usual rituals and memories are spottier, but to outward appearance I was strong. In the ultimate act of cowardice, to avoid my grieving family, when given the choice I went to school the next day. I pushed away any efforts from teachers to give condolences; I didn’t want to hear it. I didn’t want to feel it. All my classmates knew. I had called one the afternoon before. “Guess what? The weirdest thing happened today. My dad died”.

I wanted to see the body.

I needed to see the body and was refused. He was in the water too long, bloated to the point that the suit could not fit even after the morticians had done their best. Only our priest in a moment of strength that could only come from faith looked upon the ruins and confirmed that the shiny coffin in the corner contained my dad. I didn’t believe him. I no longer had faith in the agent on earth of a god who had allowed this to happen. It could have been worse; one of the others had been decapitated, his body destroyed, becoming, literally, fish food. His half-open casket showed what was recovered, a perfect head sitting atop a sawdust-filled suit.

His funeral was standing room only. My uncle, so estranged from Daddy in real life, threw himself sobbing across the casket crushing the flowers and causing the petals to litter the aisle as the pallbearers carried it from the church. During the drive to the cemetery, my brother and I turned, kneeling to look out the back window, proud to watch the seemingly endless line of cars snake behind us. A confirmation that this man had mattered to more than just us.

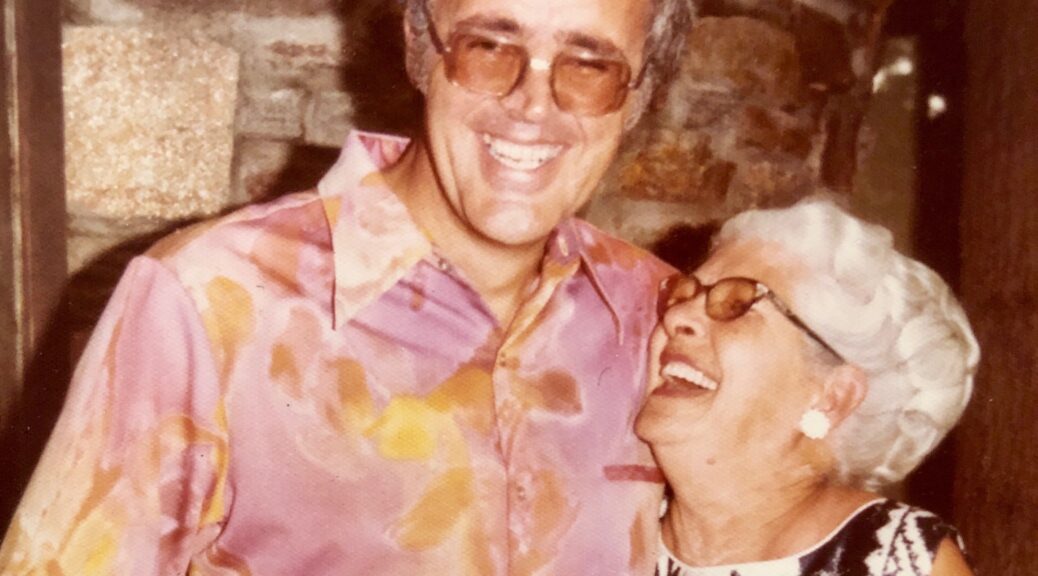

It saddens me that my actual specific memories of Daddy are more related to his death than his life, but what does remain, even stronger 42 years later, is the “feeling” of him. His love for me, his belief that I “would be fine as an adult” has carried me through my life; given me hope when otherwise there would be none. His joy and sense of fun, his love for my mother, his creativity and work ethic gave me a road map that even while I took the scenic route to adulthood guided me toward where I wished to be.

At this point in time, we are surrounded by the constant threat of illness and death. We receive the daily worldwide totals of lives lost via our phones, or Facebook, just as past generations were informed through newsreels, the radio or from the trusted voice of Walter Cronkite.

An oddity of grieving and loss is that one can ask what is better?

To see a loved one waste with illness or dementia; to have them stolen from you piece by piece, or in one instant; they were here and now they’re not? When you read this, so many of you will still be so fresh in your grief.

Feeling isolated even while sharing in a worldwide event, it may not be encouraging to know you will miss them forever, but the truth is you will.

The other truth is that it’s OK.

You will be OK.

With love,

Liesel

After my last class, I went to the parking lot to meet up with the rest of the moonbuggy team and our physics teachers. We piled into two rental vans, one of which was hauling a trailer with the moonbuggy inside. Then we set out on the four-hour drive from Suwanee, Georgia, where our high school was located, to Huntsville, Alabama, where the Space Center was hosting the moonbuggy race.

After my last class, I went to the parking lot to meet up with the rest of the moonbuggy team and our physics teachers. We piled into two rental vans, one of which was hauling a trailer with the moonbuggy inside. Then we set out on the four-hour drive from Suwanee, Georgia, where our high school was located, to Huntsville, Alabama, where the Space Center was hosting the moonbuggy race.