By Vanessa Reid

“Go on, stupid! Pick your straw,” said Burl. “I ain’t got all day.”

Teddy stared up at the boy who was at least a head taller than he was. He looked into Burl’s black eyes and thought how this was an impossible situation since Burl was making him choose a straw in order to decide who had to go into the old Walmouth place and Burl had most certainly rigged it so Teddy would select the dreaded small straw.

Burl’s cronies Paulie and Little Man had already chosen their straws and miraculously, lady luck had been with them. They grinned on either side of Burl Bogle, the biggest, meanest bully at Grover Cleveland Middle School. Teddy sighed and selected a straw. It was the short one.

Little Man danced around as he hooped and hollered at the top of his lungs. Paulie stood by Burl, with a quiet, slick smile. Burl grinned so hard he looked like a puppet, his face split in half by crooked yellowed teeth. “Well, the straw says you go in, Tumor Teddy. Whatta you know about that? Are you gonna go in like a man?” Burl snorted, “or are you gonna be a pansy like you usually are? Do we have to put you in that old shithole, Tumor Teddy?”

Teddy sighed. He knew this day would come. He could have counted on it like Salisbury steak on Wednesday and church on Sunday. He knew that he had no choice. “I’ll go,” he said solemnly.

Burl looked disappointed. “No tricks, Teddy. Do you hear? Don’t go sneaking out the back or something. You stay in there until we tell you to come out.”

Teddy nodded, pocketed his straw, and turned to walk up the steps of the old Walmouth place. He hesitated for a moment taking in the dying house. Once a stunning Victorian with two turrets and a bronzed cupola, its expansive porches sagged, its paint peeled, and its broken windows squinted at Teddy.

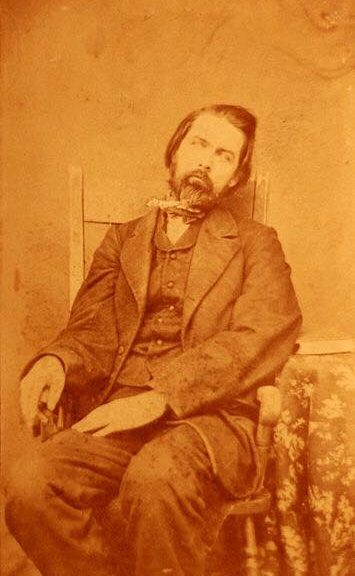

Every Halloween, kids dared each other to enter to see if the ghost of the owner, Mr. Wally Walmouth, still walked its halls. The story went that old Wally Walmouth killed himself in that house when he found out his son died in combat. Kids said the authorities didn’t find his twisted and torn body for over a week. They said he took a swan dive off the upstairs balcony and broke every bone in his body, and now, he wouldn’t leave until his son came back.

Today wasn’t Halloween, however. It was only April, a special treat just for Teddy, courtesy of Burl Bogle. Big Butt Bully Burl, Teddy thought darkly.

He walked up the front steps which crackled with each footstep. He stood in front of the front door and he hesitated. Teddy turned his head toward Burl and asked, “Are you sure you want me to do this?”

“You’re not a pansy. You’re a pussy! Get your ass in there, Tumor.” His sidekicks giggled.

“Yeah, pussy. Get in there, Tumor!” Little Man croaked. Burl gave him the side-eye. Little Man stopped smiling.

Teddy hated that nickname. Burl gave it to him in the fourth grade after Teddy’s father died from a brain tumor. His grief made him quieter than he already was, and in addition to his small size, Burl seized upon Teddy like a new toy. Burl had beat him up too many times to count, he stuck his head in the toilet at least once a week, and once even made Teddy eat worms in front of Lavender St. James, the prettiest girl in school. Teddy was so upset that he peed himself. It was the second-worst day of his life.

Teddy reached for the doorknob and after a couple of tries, shoved the door open. He walked in slowly and closed the door behind him.

Paulie grinned. “He’s gonna come running out like a pussy, right, Burl?”

“Oh, sure he is. Right, Burl? He’s gonna come running out and oh—he’s gonna pee himself, even. Right, Burl?” Little Man echoed, jumping up and down.

“Shut the fuck up, you two,” Burl said. “Yeah, he just might pee himself,” Burl said to himself softly. He grinned wider.

The three boys stood watching the silent house for what seemed like a half an hour. “M- maybe we should call him out, huh Burl?” Little Man asked.

“Shut up!” said Burl. “Just give him a second. He ain’t been scared enough yet.” Burl squinted at the house, frowning. “What the hell is he doing in there, anyway?”

Seconds later, they heard a loud crash followed by a thud. It seemed to echo through the house’s halls and spill out of the broken windows. Then, Teddy screamed. “Help! Help me, please.” There was uncomfortable desperation in Teddy’s voice, and the boys could hear him begin to sob.

“What the hell?” Burl said. Paulie and Little Man just stared at the house, mouths hanging open.

“Please, Burl, I’m hurt. I need help,” Teddy called through a broken, dirty window, but the boys couldn’t see anything inside.

“Are—are you gonna go in and help him?” Little Man asked. Paulie looked nervously at Burl, waiting for his answer.

“I ain’t going in there. We’re going in there. And we ain’t going in to rescue Tumor. We’re gonna make sure he’s not pulling something. Then, we’re gonna kick his ass and lock him in a closet for a while. If he’s pulling something, he’s about to learn real fast that you can’t mess with Burl Bogle. Come on!” The other two boys exchanged worried glances.

Burl headed up the steps to the front door, then turned around to see Paulie and Little Man still standing in the weeds of the front yard. Paulie looked grave. Little Man looked terrified.

“Get your pansy asses up here now, or I’m gonna lock you two in the closet with Tumor!” The boys walked up the steps and Burl gave the door two sharp shoves before it opened. Then, the boys walked in, leaving the door cracked open behind them.

—

The inside of the house was just as they suspected: dark and decrepit. There were old-fashioned parlors filled with sheet-covered furniture on either side of the foyer which faced a long, dim hallway. Above them on the second floor, a horseshoe staircase spilled down either side onto the landing below, shreds of rotting green carpet dotting the steps.

“Help me, please,” sobbed Teddy from somewhere up above. The boys looked at one another, relieved not to have to walk down the dark hall in front of them, and then they headed up the stairs on the left.

Once they reached the open hall above, Burl shouted, “Where the fuck are you, Tumor? You better not be jerking us around!”

“Here! I’m here,” Teddy called from a room to the left. “I’m hurt.”

The other boys looked at one another and Burl led the way to the door to the left. He reached for the doorknob and then stopped.

“What is it, Burl? Is he crying for his dead dad or something?” Little Man joked. Burl shot him an angry look and then turned his attention back to the door.

“Be quiet!” Paulie hissed. “Can’t you hear that?” Paulie jerked his head toward the door. Little Man, silenced, leaned toward the door to listen.

The boys could hear a deep male voice coming from the other side of the door but couldn’t make out what it was saying. “Yes,” Teddy said to someone. “Yes. Yes, okay.” The man’s voice continued but the boys still couldn’t understand it. “I know, you’re right,” Teddy whispered, almost too low for the boys to hear.

Burl flushed. “What is this? Some joke? I’m gonna kill that kid!” He threw the door open and the three boys rushed in. They found Teddy sitting on a sagging couch next to a broken window, the flimsy sunlight creeping in, and on the other side of the moldy velvet seat sat an old man in a strange suit.

“What the…?” said Burl.

“You were right when you said they would come,” a smiling, uninjured Teddy said to the man next to him. “You are a wise man, Mr. Walmouth.” Teddy turned and smiled at the other three boys. “Boys, I want you to meet a friend of mine. This is Mr. Walmouth and you are in his house.”

“Ah! The infamous Big Butt Bully Burl. We have been expecting you, son.” Burl stood in front of the other two boys and paled as he watched the old man in disbelief.

“What the hell?” Burl said shakily. “You…you ain’t Walmouth. He’s been dead forever.” Little Man had begun to sob and Paulie tugged at his sleeve as he stepped back to the door.

Mr. Walmouth grinned humorlessly exposing rotted teeth and tiny white worms crawling through the blackened holes. One fell onto his dusty lapel and wriggled there before sliding into his lap. “Yes, Burl, I have.”

Little Man screamed and Paulie pulled him out of the door and down the stairs. Burl swayed on his feet as a wet stain spread on his crotch.

“So, Burl,” Mr. Walmouth said. “It seems we need to have a little chat about my son Teddy, here.”

Burl shook his head. “No, please no.”

“Oh, yes. I insist.” The door slammed shut behind him.

—

Teddy closed the front door and skipped down the steps of the old Walmouth place. He turned back and looked at the house with fondness. He had been coming here since January when Burl had become too much and the grief had become more than he could bear.

He thought that it would be the right place to take his own life so his mother wouldn’t have to find him, but the day he chose to die turned out to be the first day that he had really lived in a very long time. That day, he met old Wally Walmouth and they became friends. They had much in common—especially their grief—and it was nice to be understood for once.

Teddy remembered the day he entered the house and climbed to the top of the staircase. He was crying as he stood on the railing looking down and the floor below. At that moment, Teddy’s pain crested. He bent his knees and was preparing to jump when an unseen blow knocked him backward to the floor of the second-floor landing. When he looked up, Mr. Walmouth stood above him frowning. He had never seen a ghost before but Teddy wasn’t scared.

Mr. Walmouth guided Teddy to the parlor where they sat and talked for hours. Talked about the death of Mr. Walmouth’s son and his own suicide. He had jumped from that very banister. They talked about Teddy’s father, and how that sorrow was an unending curse. Mr. Walmouth’s grief had overtaken him just like Teddy’s.

Mostly, they just talked about mundane things like fishing and the books they both enjoyed. Teddy learned that Mr. Walmouth and his boy used to fish together after church on Sundays just like Teddy and his father. Soon after that, Mr. Walmouth began to call Teddy “son” which was a comfort to Teddy. Just like a protective father, when Teddy told Mr. Walmouth about Burl and the other boys, Walmouth said not to worry about them, as long as Teddy kept coming back to visit.

Now, Teddy was ready to live his life in peace. He was so grateful. Grateful for Mr. Walmouth’s friendship and guidance. Grateful he didn’t hurt his mother more than she had already suffered. Grateful that it was all over. Burl would never bother him again, just like Mr. Walmouth promised. The other boys wouldn’t mess with him either. Maybe they could even be friends. Teddy would come back soon to visit and to thank Mr. Walmouth, but not until they found Burl’s body and all of that business was behind them. He almost couldn’t wait to go to school tomorrow.

Teddy paused in the overgrown yard, took the short straw from his pocket, and stuck it in his mouth, smiling as he headed home.