By Jon Sokol

Larry watched as his young friend squinted at an open can of tuna.

“This product not for human consumption,” Deke read aloud.

He turned the can around to show Larry the picture of an orange cartoon cat licking its mouth.

Deke tossed it into the smoky campfire the two men had built to keep away the god-awful South Georgia mosquitos and pissed-off yellow flies. He took another bite from his half-eaten cat food sandwich and tossed the rest into the flames. Deke would cry if he were alone.

Instead, he fished out a tin of Copenhagen from his blaze orange timber cruising vest and smacked it against the heel of his hand. He lifted the metal top and held the cardboard container to his nose savoring the pungent odor of the snuff.

Larry fished around in his brown paper bag and pulled out a small Tupperware bowl filled with red Jell-O cubes. He lifted the top and shook the gelatinous mass until it landed with a plop in the dirt between his worn-out boots.

Deke looked over at him and shook his head.

“Dammit, Larry. Every day I watch you dump that shit out on the ground. Why don’t you tell Mrs. Soo you don’t like that mess?”

He placed a wad of dip on his tongue and rolled it around his mouth until it nestled in the familiar spot between cheek and gum.

“Believe me, bud. It’s just better this way.”

Larry snapped the lid on the plastic container. He took a long drink from a warm can of Diet Rite and balanced it next to him on the log.

Larry was a veteran. He had served in the 7th Cavalry Regiment in Korea, but he never talked about it, even when he was ripped on bourbon. Back then, the brutality he witnessed didn’t feel right, even for a once narrow-minded Georgia boy. He would just shake his head when asked about the war and say, “It was so fucked up. Nobody knew what they were supposed to be doing.”

The war atrocities that Larry saw in Korea haunted him still. He credited Soo-Min with saving his once bigoted soul, but privately, he attributed much of his change of heart to his disgust at his unwillingness to stand up to the malicious slaughter of those innocent refugees, almost all women and children.

After two tours of duty, he returned stateside with his Korean bride and enrolled in the School of Forestry at Abraham Baldwin Agriculture College in Tifton. Two years later he was living back in his hometown, cruising timber and running planting crews for the pulp mill up the road in Savannah.

That had been over forty years ago. Now he was teaching young Deke the ropes. It was time for him to turn in his cruising gear and hang up his snake chaps. In two weeks, he would turn sixty-five and have his modest retirement party on the same day. He and Soo-Min were set to haul their horse trailer and otherworldly possessions to northern Colorado. The thought made him smile. He loved his community, but he was disgusted with its excruciatingly slow progress. Still perturbed at the double-takes people gave him and his wife. He was ready to move on.

He was going to miss Deke, though. Most weekdays for the past six months, he and Deke had worked together cruising timber from sun up until the early afternoon, then checking on loggers, site prep operators, and fertilizer contractors from the air-conditioned comfort of a company-owned Ford pickup.

Deke was from north of Atlanta and fresh out of college. Twenty-two years old and fifty thousand in debt to the U.S. Government who had carelessly loaned him the money to go to the University of Georgia. He told Larry that, in Forestry 101, he was taught how he could save the planet and all its endangered species by applying well thought out silvicultural treatments to bountiful forests. He said they never told him he’d be humping through pine plantations in hundred-degree weather and moving to a small town known only for having a shitty sawmill and a string of church burnings.

The two men sat on the log together and talked about Larry and Soo’s recent trip to Atlanta to see the Olympics. Larry told Deke how bittersweet it was to see Muhammad Ali, once unbeatable now trembling with Parkinson’s, light the cauldron. And how excited Soo was when Michael Johnson won the gold medal in the 400 meters. But Deke was clearly not interested in the conversation.

“How’s Jill doing?” Larry asked before tossing a handful of pecan halves into his mouth.

Deke swatted at a mosquito, stood up, spat in the fire, sat back down. “She’s going to Minnesota to see her sister.”

“Well that sounds fun.” Larry would not look at Deke.

“She says she ain’t coming back.”

Larry took off his round eyeglasses and wiped them with a faded red bandana. “You sure?”

“I’m sure. She said she didn’t want to be married to a homophobic racist anymore.”

“Hmm. Sounds like she’s pretty sure.”

“What do you think about that, Larry?”

Larry raised his eyebrows and blew out a long horsey sigh. He put his glasses back on wrapping the wire legs around his ears and stuffed the bandana in his back pocket. “Those are some pretty serious allegations.”

“Yeah, no shit.” Deke’s leg bounced up and down like an erratic jackhammer. “The last argument we had was whether Tupac getting shot dead was a good thing or a bad thing.”

“I’ll guess which side you came in on.”

“Look, I might have some opinions, but I wouldn’t say I’m racist. That asshole’s songs were about killing white people.”

Larry put up his hands as if to stop traffic. “I can’t say I ever heard any of the man’s music, but saying that anybody deserves to die is a bit harsh.”

Deke crossed his arms and spat tobacco juice. The fire sizzled.

“Look, here’s the deal,” Larry continued. “Most everybody I know in this damned town is a homophobic racist. Preachers, teachers, the man who owns the bank, my own momma. It’s just the stew we swim in.”

Deke looked him in the eyes then dropped his gaze back to the fire.

“The good news,” Larry said, “is that you didn’t come out the womb that way. It ain’t as natural as people let on. I mean, it’s up to you, but you can change.”

“I don’t know, Larry. She’s got her mind made up.”

“Oh, no. She’s gone. You’ve screwed the pooch on that one, son.”

Deke removed his ball cap and clawed his fingers through his dirty blond mop of hair. “I haven’t even told my folks yet. What am I supposed to say to them?”

“Maybe ask them why they raised you to be so damned hateful.”

“Come on, man. You know I’m as nice a guy as anybody. You and me get along good, don’t we?” Deke’s eyes reddened with anger.

“Yeah, but I’m a straight white dude.”

Deke jerked to his feet. “Fuck you, Larry.”

“Settle down a minute, son,” Larry said. Deke turned his back to the older man. “So far, your education has been mostly in classrooms, Sunday school, and hanging out with your folks,” Larry continued. “You’re out on your own now, and you’re going to find out that things are not as simple as you were led to believe.”

Deke shook his head slowly. “What the hell are you talking about, Larry?”

“I’m telling you that you need to think long and hard before coming up with your opinions. Put yourself in other people’s shoes before you spout off some bullshit you learned watching cowboy movies.” Larry tilted his head to the side. “Jill called you out on that, didn’t she? Said to stop being John Wayne and to listen for a change.”

“Wait,” Deke said. “How did you know that?”

“Kid, I know more about you than you do.” Larry stood in front of Deke and looked him in the eyes. “I’d love to give you some life-changing advice, but I know you. You’re going to have to live your way through it.”

Deke broke eye contact. He walked to the fire and kicked dirt over it, extinguishing the flames.

“You’re going to have a lot of regrets one day,” Larry said. “Regrets you’re not counting on now. When that happens, don’t beat yourself up about them. Just be glad you can recognize them as regrets.”

Larry turned back to the log and drained the rest of his soda. “In the meantime, just try not to be a dick to people.”

“Jesus,” Deke whispered. He stomped up a cloud of powder dust to the truck and climbed in behind the steering wheel and slammed the door. The engine made an initial screech and settled into a throaty purr. Deke glared through the windshield at nothing in particular. He rolled down the window and spat.

Larry stretched his wiry frame. He squinted as he looked westward into the cloudless blue sky. Turkey buzzards circled overhead, drawn to a stench that only they could smell. Probably some dead armadillo or possum. Something not fit for human consumption.

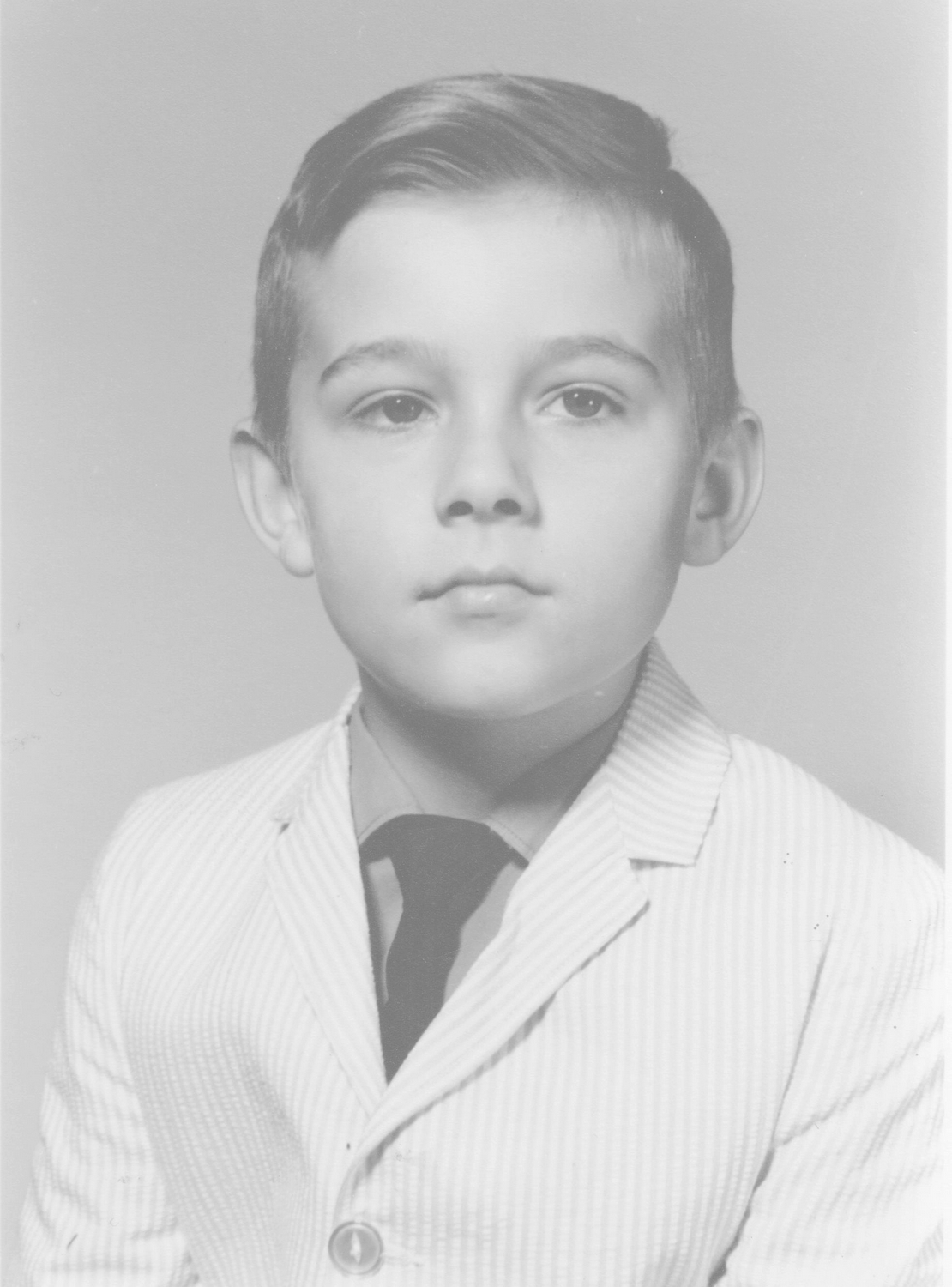

Here’s me in 1961, the sad first-grader from Illinois, arrived with his grandparents for a week with Virginia mountain kin. He shuffles from the gas station, peels the wrap off a Popsicle. Cuts across the outfield, past the tomboy who fist-smacks her mitt, waiting for the play.

Here’s me in 1961, the sad first-grader from Illinois, arrived with his grandparents for a week with Virginia mountain kin. He shuffles from the gas station, peels the wrap off a Popsicle. Cuts across the outfield, past the tomboy who fist-smacks her mitt, waiting for the play.